Discovering Oscar Gustave Rejlander at Dimbola

One of the big, big revelations of my research-phase around Julia Margaret Cameron was the discovery of Oskar Gustave Rejlander - the Anglo-Swede photographer who had worked with Charles Darwin, - using photographs to illustrate his book on The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (Darwin, 1872), and who had worked extensively with the Wet Collodion process and - importantly - mentored and helped Julia Margaret with her experiments in learning about the technique, and about photography generally. Importantly, Rejlander began experimenting with composite photography - or art-photography as it was later called, kick-starting, with Henry Peach-Robinson, the Pictorialist tradition in photography. Rejlander’s most famous piece is The Two Ways of Life (1857) a magnificent and large-scale composite of several ( actually 32 individual prints) of his preparatory wet-collodion plates montaged together. Exactly how he did this is unknown - Rejlander describes the basics, but it's still unclear: Rejlander and Peach Robinson’s technique as I saw it in mediainspiratorium:

Oscar Gustave Rejlander: The Two Ways of Life composite photograph 1857

“Peach Robinson and Oscar Rejlander were the first to explore the potential of making multiple individual negatives of an imaginary scene and then reconstructing it by compositing each printing together in one final positive print. In this case, and in Rejlander’s spectacular The Two Ways of Life (1857), the artist-photographers were composing an imaginary image, casting, styling and setting the component poses before making the final artwork. David Octavius Hill, working with the photographer Robert Adamson, the Scottish pioneer (also a painter before he discovered photography) had made individual photographic portraits of the 474 sitters in his gigantic First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland (1843), but had then composited them using traditional oil-painting techniques. Rejlander and Peach Robinson then were the first to realise the true advantages of photography as a compositing medium – some 130 years before such compositing became commonplace in tools like Photoshop (and of course in digital video compositing tools like After Effects). Even before these brilliant software apps, this kind of digital compositing was available in early industrial reprographic paintboxes and electronic page-make-up and compositing machines like the Crosfield (Crosfield Lasergravure Electronic Page Composition system c1979) and Scitex (Scitex Response300 1979) – very expensive mini-computer based systems.

Back in the 1860s Rejlander and Peach Robinson were making exposures on glass plates (using the wet-collodion process) then presumedly making prints on paper, assembling these into their intended composition by careful cutting and pasting, then rephotographing the resulting image to make a final print. Armed with this experience – and his most successful composite Bringing Home the May – Peach Robinson went on to write The Pictorial Effect in Photography (1867), his manifesto for the Pictorialist movement that he founded. This was a reasoned argument to allow photographers the same freedom as painters to adjust and manipulate their images after exposure, much as a painter could retouch and revise an oil-painting over several months.”

“Peach Robinson and Oscar Rejlander were the first to explore the potential of making multiple individual negatives of a scene and then reconstructing it by compositing each printing together in one final positive print. In this case, and in Rejlander’s spectacular The Two Ways of Life (1857), the artist-photographers were composing an imaginary image, casting, styling and setting the component poses before making the final artwork. David Octavius Hill, the Scottish pioneer (also a painter before he discovered photography) had made individual photographic portraits of the 474 sitters in his gigantic First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland (1843), but had then composited them using traditional oil-painting techniques. Rejlander and Peach Robinson then were the first to realise the true advantages of photography as a compositing medium – some 130 years before such compositing became commonplace in tools like Photoshop (and of course in digital video compositing tools like After Effects). Even before these brilliant software apps, this kind of digital compositing was available in early industrial reprographic paintboxes and electronic page-make-up and compositing machines like the Crosfield (Crosfield Lasergravure Electronic Page Composition system c1979) and Scitex (Scitex Response300 1979) – very expensive mini-computer based systems. Back in the 1860s Rejlander and Peach Robinson were making exposures on glass plates (using the wet-collodion process) then presumedly making prints on paper, assembling these into their intended composition by careful cutting and pasting, then re-photographing the resulting image to make a final print. Armed with this experience – and his most successful composite Bringing Home the May – Peach Robinson went on to write The Pictorial Effect in Photography (1867), his manifesto for the Pictorialist movement that he founded. This was a reasoned argument to allow photographers the same freedom as painters to adjust and manipulate their images after exposure, much as a painter could retouch and revise an oil-painting over several months.” (from my mediainspiratorium)

(Bob Cotton: Rejlander in Mediainspiratorium in https://mediainspiratorium.com/1800-1920/

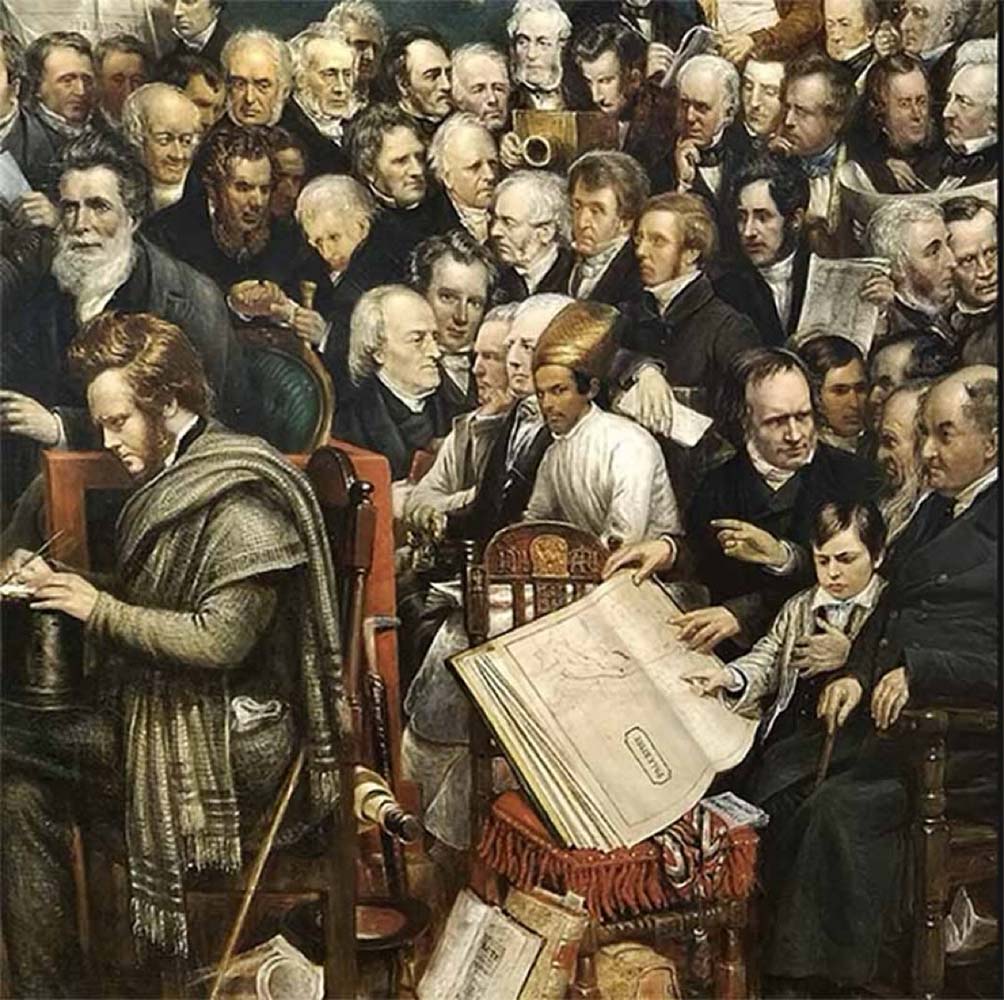

So if Peach Robinson and Oscar Rejlander together founded Pictorialist or Art-Photography, then Rejander’s adult pupil - Julia Margaret Cameron - learned some of these lessons while being tutored by Rejlander and others in the early 1860s - her use of soft-focus, her manual retouching of her Wet Collodion plates, her ‘theatrical’ and ‘classical’ styling and posing and composition of subjects - all a product of influences by the Pictorialist innovators. The earliest example of this kind of photo-montage (though roughly contemporary) is of course Hill and Adamson: Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill: Disruption of Church of Scotland (The First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland; signing the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission - 18th May 1843 (D.O. Hill RSA).

The Disruption painting by Robert Adamson 1863 - from individual, composited photo-portraits made by David Octavius Hill 1843

So the ‘Disruption Painting’ took oughly twenty-three years to complete, finished in 1866, supposedly sometime after the original photographic portraits of all the attendees was completed - we don’t know exactly the chronology of this unique art-work. The big questions are: did Hill use the Wet Collodion process - not published by Scott-Archer until 1851? And did Adamson AND Hill make the individual photo-portraits AND montage them together before Adamson undertook the task of producing the painted version? It definitely looks like a montage, in which case think of the time it took to create the 457 individual portraits using the wet-Collodion process - and printing them! And then cutting them out! and then montaging them into one huge photo-montage…

Look at a detail of Adamson’s oil-painting (this is centre left) - remember all the colour here is painted - it includes a portrait of Octavius Hill with his sliding-box camera - upper centre. Note that these are probably - definitely in my opinion - composited monochrome photo-portraits, though the subjects all seem to be looking in different directions - you might have expected people when their portraits are made to be looking directly at the camera - and there’s a disparity of scaling not accountable by perspective - look at the central group - the coloured priest looks out-of-scale to his neighbours - was itbecause the compositing of individual portraits was taken at various times in 1843 or added sometime later? - the painting from these portraits wasn't finished until 1866 - or was it Adamson’s oil-painted interpretation of these images? Remember the bulk of these portraits are (presumedly) dated 1843 - though the wet-collodion process wasn’t perfected until 1851 - by Frederick Scott-Archer and the photo-printing method - either Salt-Print or Albumen-Print (from 1847) or Salt-Print (from c1839, invented by Fox-Talbot). So it would be good to know exactly what techniques these two pioneers used. Though not a photograph in itself, this is probably the first example of ‘pictorialist’ photography - the artistic adornment or extension of photography. And consider the time factors involved - preparing a wet-collodion glass-plate before exposure would take 15-20 minutes in itself - first washing with a Saltwater- solution, then sensitising with Silver Nitrate - then exposing the sensitised plate in a camera with the then contact-printing in direct sun-light (etc) - and this for everyone of the 457 individuals included in the final picture. This is an enormous task!

Anyway, forgive this little mini-essay, the point is that Julia, under the mentorship and tutelage of Rejlander, Herschel, Wilkie-Wynfield, and George Watts - was ideally placed to to be innovative and experimental in her late-in-life discovery (age 49) and exploration of photography.

Two of Julia's experiments with pictorialist photography - more to come on these...